Case study

Product innovation to reduce consumer carbon emissions

Can digital products encourage consumers to reduce their carbon emissions? We worked with Octopus Energy's product innovation team to explore this question by developing and testing product concepts.

Technology (alone) will not save us

According to the UK’s Committee on Climate Change (CCC), behaviour change in individuals, households and businesses is essential for achieving climate and environmental goals. We simply can’t rely on new technology, government and big business to solve the problem alone.

But how can we persuade people to change their habits? And what role is there for new products and services in nudging people towards Net Zero?

Green ideas

In late 2019 Will and Julius, founding partners at Octopus Energy Hatchery, were grappling with this question.

They had ideas. And, having held senior positions at Ovo, they knew the energy sector inside out. But they were less practiced at customer development and user research, and they wanted to base their development efforts on a solid understanding of their potential users.

In initially there were three ideas on the table:

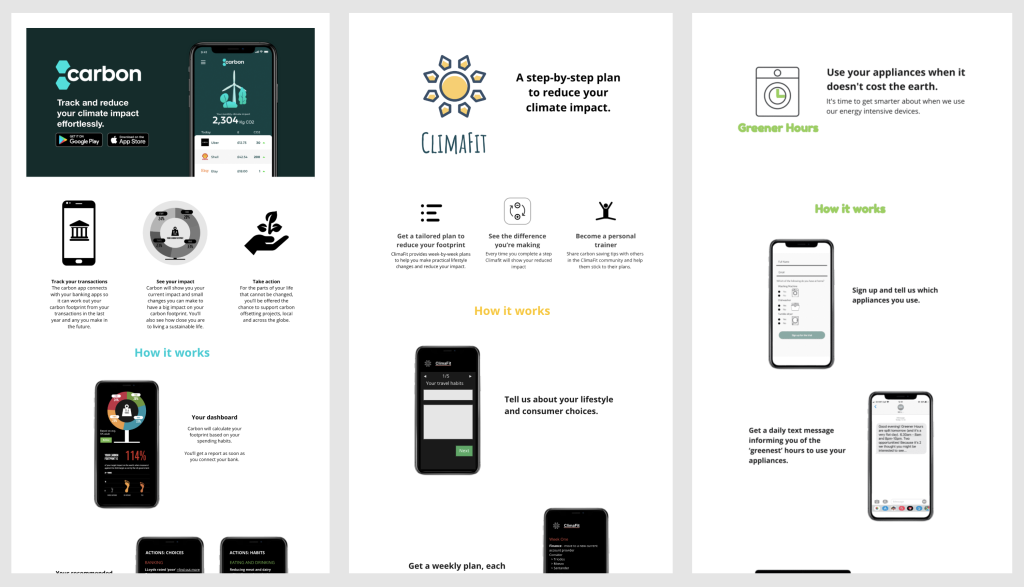

“Carbon” – An app that uses spending data (via Open Banking) and energy consumption data (from smart meters) to recommend actions to reduce the user’s carbon footprint.

“Climafit” – An app that offers users a week-by-week carbon reduction plan based on an upfront assessment, delivered in a fitness regime style.

“Greener Hours” – A service that helps users reduce their carbon footprint by using energy when the grid is at its greenest. (The proportion of UK electricity supply fed by renewable energy varies throughout the day and in different locations).

Which, if any, of these had the potential to be a viable product? What other opportunities and ideas might emerge from exploring this space?

For us, it was the perfect brief.

Approach

What would have to be true for this to work?

We began by systematically stepping through their ideas. Who would use these services? Why would they use them? How would they use them? How would they find them? How would they make money? What alternatives already exist?

We used Empathy Maps and a Lean Canvas to facilitate the conversation, then mapped out the assumptions we were making and considered ways to test them.

For example, for the Carbon app, we needed to know if users would be willing to share their spending data, whether they would take the carbon-cutting recommendations provided by the app seriously, and whether they would take action.

We also needed to test the business model – how would they react to the idea of paying to offset their remaining carbon footprint?

Understanding needs and gauging reactions

We knew we couldn’t answer all these questions in one go, but we agreed on two initial rounds of research.

In round 1 we kept things broad, and conducted a two part interview.

Part 1 was generative – focusing on how people think about climate change and the frustrations they have when considering actions they can take to reduce their emissions.

Part 2 was evaluative – gauging responses to each of the three concepts we had. (We find it’s useful to show more than one concept in a session, because it enables us to compare interest levels. Sometimes we even insert dummy ideas for this purpose.)

Judging customer interest in new products in interviews is hard because people want to please – so we added a little test. At the end of the interview we asked the participant to email us for early access to the Beta. Sure enough, only a third of the participants who seemed enthusiastic in the session actually got in touch.

By the end of round one we’d created a prioritised list of user needs that we were confident in and had decided that the Carbon App was best placed to address those needs.

Users liked seeing a breakdown of their emissions and recommended actions. And they were happy to connect to Open Banking to be able the app to dynamically track spending.

Testing the prototype

In round 2 we produced a prototype of the Carbon app. We really wanted to see how people would react to seeing their actual carbon footprint and real recommendations for how to reduce it. Would they sit up and take notice? Would they question the data? Would they take notes?

So when booking calls with participants we mimicked the onboarding process by asking them to fill in a brief questionnaire and supply (redacted) bank statements. Julius then produced a realistic Carbon footprint assessment and a real set of recommendations for each participant, which we presented in a different version of the prototype for each participant.

What did we learn?

Here are some of our takeaways from our research in round 2:

Stay positive – When presented with their footprint (which is, in most cases, far too high to be sustainable) some people will react defensively, so stay positive and reassure people that they are not alone, and there’s lots they can do to improve.

Break it down – Some people will want to dig into the detail to ascertain if their footprint is accurate. And some will happily to take steps to make it more accurate (e.g. by uploading receipts). So make that easy for them.

Provide a target – People need to know what their aiming at. What level of emissions is OK? Our app designs only showed the global average, which some felt was ‘unfair’ given that much of the world has less developed economies.

Highlight quick wins – People wanted to see where a simple change would make a meaningful difference, so they could act immediately. Strike while the iron is hot!

Go beyond the obvious – People were expecting new actionable ideas for reducing their footprint. Suggesting they buy electric car was not thought to be helpful.

Switching is welcomed – People liked to compare the emissions of supermarkets, airlines and energy providers and appeared happy to switch.

Offsetting requires trust – Some people will pay to offset their emissions, if they are convinced that their money is being used well. So make sure the projects are well described and credible.

Keep prodding – People said they would need to be reminded to think about their carbon budget when making decisions.

Outcome

Following the research we all felt positive about the market for a carbon tracking service like Carbon.

We had seen users get excited by the prospect of understanding and reducing their emissions, and they were tempted by the chance to offset them.

However, using spending patterns at the level of the vendor rather than the product, to generate estimated emissions felt like a real compromise and was not a compelling proposition. So we decided to put the idea on hold.